what measurement is used to study blood pressure

Abstruse

Background

The US Preventive Services Task Strength recommends blood pressure (BP) measurements using 24-h ambulatory monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring before making a new hypertension diagnosis.

Objective

Compare clinic-, domicile-, and kiosk-based BP measurement to ABPM for diagnosing hypertension.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Diagnostic study in 12 Washington State main intendance centers, with participants aged 18–85 years without diagnosed hypertension or prescribed antihypertensive medications, with elevated BP in dispensary.

Interventions

Randomization into 1 of iii diagnostic regimens: (one) clinic (usual care follow-up BPs); (2) dwelling (indistinguishable BPs twice daily for 5 days); or (3) kiosk (triplicate BPs on 3 days). All participants completed ABPM at iii weeks.

Master Measures

Main outcome was deviation betwixt ABPM daytime and clinic, home, and kiosk hateful systolic BP. Differences in diastolic BP, sensitivity, and specificity were secondary outcomes.

Primal Results

5 hundred ten participants (mean age 58.vii years, 80.two% white) with 434 (85.1%) included in primary analyses. Compared to daytime ABPM, adapted mean differences in systolic BP were clinic (−4.7mmHg [95% confidence interval −7.three, −two.2]; P<.001); abode (−0.1mmHg [−1.6, 1.five];P=.92); and kiosk (9.5mmHg [7.5, 11.half-dozen];P<.001). Differences for diastolic BP were clinic (−seven.2mmHg [−8.8, −5.5]; P<.001); home (−0.4mmHg [−1.iv, 0.7];P=.52); and kiosk (5.0mmHg [3.8, half dozen.2]; P<.001). Sensitivities for clinic, home, and kiosk compared to ABPM were 31.1% (95% confidence interval, 22.9, forty.6), 82.two% (73.eight, 88.4), and 96.0% (90.0, 98.5), and specificities 79.5% (64.0, 89.iv), 53.3% (38.9, 67.2), and 28.2% (xvi.4, 44.1), respectively.

Limitations

Single wellness intendance arrangement and express race/ethnicity representation.

Conclusions

Compared to ABPM, mean BP was significantly lower for clinic, significantly higher for kiosk, and without pregnant differences for home. Clinic BP measurements had low sensitivity for detecting hypertension. Findings support utility of dwelling BP monitoring for making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03130257 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/testify/NCT03130257

INTRODUCTION

Elevated blood force per unit area (BP) is the leading contributor to cardiovascular events and mortality.1, ii While nearly adults with hypertension take antihypertensive medications, many are unaware they have high BP. A written report using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2018 data estimated that 23% of US adults with high BP (systolic ≥140 mmHg or diastolic ≥xc mmHg) were unaware they had hypertension and were untreated.three

For patients with loftier screening BP in clinic, US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)four and other hypertension guidelines recommend follow-up BP testing outside of clinics by 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring (HBPM), to avoid overdiagnosis and unnecessary handling.5,vi,7

Currently, ABPM is infrequent in the USA, partly from lack of availability, low reimbursement, and perceptions of lower patient acceptability.eight HBPM is an culling, simply patients need to apply validated monitors, be trained on proper use, and take multiple measurements,9,10,xi leading to questions most the accuracy of using HBPM to diagnose hypertension. BP kiosks in pharmacies or dispensary waiting areas are an alternative for HBPM, but to our cognition, no studies have compared kiosk to ABPM for making a new hypertension diagnosis. Blood Pressure level Checks for Diagnosing Hypertension (BP-Bank check) was a randomized diagnostic study comparing the accuracy of clinic BP, HBPM, and kiosk BPs to ABPM for making a new diagnosis of hypertension.

METHODS

Setting and Population

The setting was 12 KPWA primary care centers in Western Washington. Enrollment was May 11, 2017, to March iv, 2019. Study design and methods were published.12 Electronic wellness records (EHRs) were used to identify individuals aged 18–85 with elevated BP (≥138 mmHg systolic or ≥88 mmHg diastolic at concluding outpatient visit) with no hypertension diagnosis in the prior 2 years and no prescribed antihypertensive medications in the prior 12 months. EHR data were used to exclude patients with BP ≥180 mmHg systolic or ≥110 mmHg diastolic; pregnancy; life-limiting affliction (due east.thousand., end-stage renal failure); and weather condition that might make participation hard (e.g., dementia) or BP monitoring less authentic (e.g., atrial fibrillation).

Potentially eligible individuals were mailed an invitation with a written report description and $2 neb and chosen to confirm eligibility. Those willing to participate were scheduled for screening visits. At visits, a research assistant confirmed individuals had not engaged in heavy exercise, used tobacco, or had caffeinated drinks in the prior 30 min. Individuals sabbatum in a chair with dorsum back up and the upper left arm was measured with an appropriately sized gage used.11 Later on 5 minutes' residual, BP was measured twice ane min autonomously using a validated Omron 907XL monitor.thirteen

Individuals with BP ≥140 mmHg systolic or ≥ninety mm Hg diastolic on both measurements were eligible. Those with mean ≥180 mmHg systolic or ≥110 mm Hg diastolic were excluded and told to make a physician's appointment.

Randomization and Blinding

The biostatistician used R statistical software (version iii.2.2) to randomly assign patients to clinic, domicile, or kiosk groups. Randomization was stratified by clinic, age (<threescore or ≥60 years), and mean baseline systolic BP (<150 or ≥150 mmHg), with random block sizes of 3 or six inside each stratum. Except for study biostatisticians, investigators were blinded until all upshot data were collected. Participants and study staff were enlightened of group assignments.

Diagnostic Tests

The clinic group received routine care for high BP at KPWA. Participants were instructed to brand an appointment at their clinic for a BP recheck. Clinic BP measurements are commonly taken past a medical assistant using a wall-mounted aneroid BP monitor (Welch Allyn Tyco)14 or, less frequently, with a validated oscillometric BP monitor (GE CARESCAPE V100).15 For high initial BP (systolic BP ≥140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg), standard procedure is to measure out BP once again after at least 5 min.sixteen If BP is elevated once more, the patient's clinician is notified to make a program and a follow-up BP-check visit is scheduled. These steps are repeated until BP is <140/90 mmHg.

Domicile participants received a validated Bluetooth-enabled oscillometric Omron N786 BP monitor17 with an accordingly sized upper-arm gage to have duplicate measurements twice daily for 5 days: later on rising and at bedtime (full 20 measurements).18 Domicile BPs were collected by study staff via Bluetooth.

Kiosk participants were asked to measure BP using validated PharmaSmart BP kiosksnineteen at KPWA clinics or nearby pharmacies, with triplicate measurements on 3 separate days.20 Measurements were linked to participants via a kiosk smartcard and collected using the vendor'south cloud-based service.

Clinic, dwelling, and kiosk participants received verbal and written instructions. All participants received the same reminder 2 weeks after their initial visit to complete their diagnostic assignment if they had non already done and then.

Reference Standard

All participants were asked to return at 3 weeks for ABPM diagnostic testing by validated Welch Allyn 7100 ABPM (cuff size based on arm circumference, non-dominant arm),21 measuring BP every xxx min, 7AM to 11PM, and hourly, 11PM to 7AM. Patient participants and their physicians received ABPM results and were advised to follow upwards on tests that were positive for hypertension. ABPM results and communications were documented in the EHR (dwelling and kiosk BPs were not).

Outcomes

The primary upshot was participant'southward mean systolic BP for assigned diagnostic method using all available BP information. Mean diastolic BP and diagnostic accurateness were secondary outcomes. Daytime ABPM was defined as the mean of BPs collected 7AM-11PM. Nighttime plus daytime measurements were used for secondary outcomes of mean 24-h and mean nighttime ABPM. Adverse events potentially related to study participation were reported using the question: "Since your concluding research visit, take you experienced any new or serious health concerns?" BP outcomes at 6 months included receipt of a new hypertension diagnosis in the EHR (based on new ICD-10 code I-11, I-12, or 1-thirteen). Prespecified subgroup comparisons were based on potential to influence diagnostic performance: baseline systolic BP (<150 mmHg vs. ≥150); historic period (<threescore vs. ≥sixty years); arm size (<33 vs. ≥33 cm); trunk mass index (BMI as kg/m2; <30 vs. ≥30); cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk; and race.

Sample Size

With a sample size of 510 (170 per group) and bold an outcome ascertainment rate of at least fourscore%, nosotros could discover a iv.1-mmHg difference in systolic and a two.8-mmHg difference in diastolic BP between any two groups (assuming standard divergence 12.1 mmHg systolic and eight.three mmHg diastolic). BP differences and standard deviation were based on prior studies comparing clinic, home, and kiosk BP to ABPM.18, twenty, 22

Analyses

Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed among participants completing ≥one BP diagnostic test measurement and ≥xiv daytime reference test ABPM measurements.23 Group differences in the comparability of the diagnostic test systolic BP relative to ABPM (principal outcome), were assessed using linear regression models with the dependent variable defined as within-person divergence in systolic BP between the hateful diagnostic examination and ABPM measures. Models included indicators for diagnostic grouping, with aligning for historic period, sexual activity, BMI, teaching, and baseline systolic and diastolic BP. Generalized estimating equations with robust standard mistake were used to relax normality assumptions.24 Fisher protected to the lowest degree significant difference arroyo was used to protect against multiple comparisons, requiring that the omnibus exam of any differences betwixt groups was statistically significant earlier making pairwise comparisons.25 To accost bias due to missing information, a sensitivity assay was conducted using inverse probability weighting for the primary assay population simply. Group differences for diastolic BP measurement (secondary upshot) were assessed using similar methods. In exploratory analyses, we restricted analyses to those defined a priori as adherent to assigned diagnostic regimen, based on prove for home and kiosk,xviii, 20 and usual care for clinic: clinic, 1 outpatient dispensary BP; home, xvi measurements over ≥4 days; kiosk, 6 measurements over ≥2 days. Result modification by baseline BP and participant characteristics (east.g., historic period, race) was assessed by including interactions betwixt diagnostic method and subgroups. Bland-Altman plots were used to show understanding between diagnostic BP measurements and ABPM.

Secondary analyses assessed the diagnostic functioning of clinic, home, and kiosk BP measures by estimating the sensitivity and specificity of each diagnostic method compared to the reference standard, daytime ABPM. Hypertension diagnosis according to the reference standard was defined as hateful daytime ABPM systolic ≥135 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥85 mmHg. For each diagnostic method, we defined a positive exam as hateful diagnostic BP above a threshold for hypertension of systolic BP ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg for clinic and systolic ≥135 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥85 mmHg for home and kiosk.26, 27 Sensitivity was estimated by fitting a logistic regression model with an indicator for a positive test outcome as the dependent variable and diagnostic group as the dependent variable among participants with hypertension past ABPM. Specificity estimates were similar merely with an indicator for a negative test result equally dependent variable and diagnostic grouping as independent variable among participants without hypertension past ABPM. We also estimated positive and negative predictive values, and positive and negative likelihood ratios for each group. Exploratory analyses estimated these diagnostic metrics for a multifariousness of systolic/diastolic pairs of thresholds for defining a positive diagnostic exam using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and computed area under the bend (AUC) separately for systolic and diastolic BP. AUC was non calculated for the bend based on systolic/diastolic pairs, because there is no way to vary the paired thresholds across the range of possible values.

Additional exploratory analyses included diagnostic performance assessment using the following: (a) mean 24-h ABPM instead of daytime ABPM every bit the reference standard with hypertension thresholds of hateful systolic ≥130 mmHg and mean diastolic ≥80 mmHg and (b) American Higher of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommendations for diagnosing stage 1 hypertension (≥130 mmHg systolic or ≥lxxx mmHg diastolic for mean daytime ABPM, clinic, home, and kiosk BP).5, 26 Analyses used Stata statistical software (release 15). Statistical inference used 2-sided hypothesis tests, and significance threshold P<.05.

RESULTS

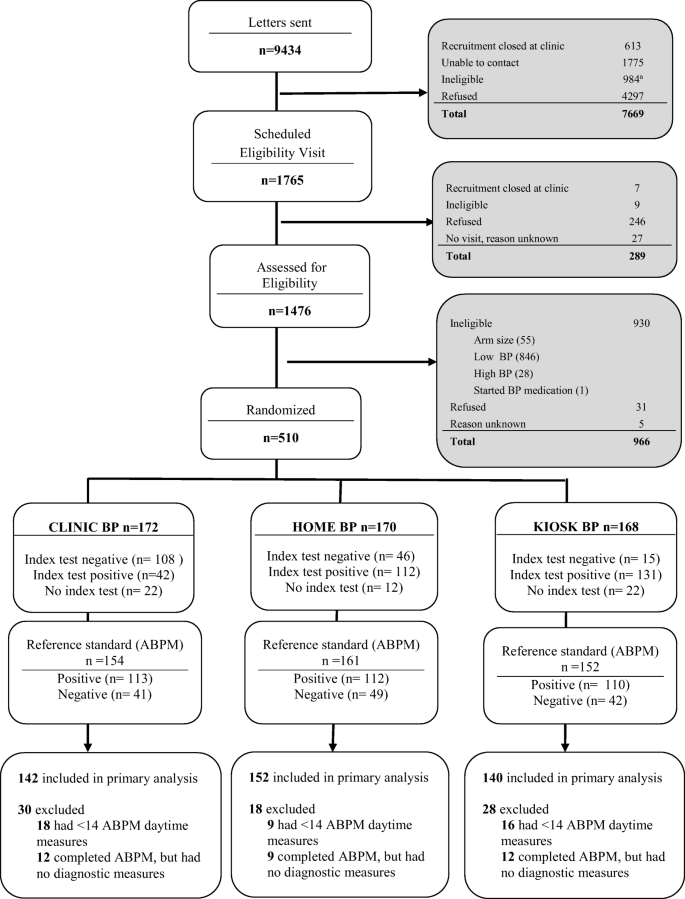

We mailed 9434 invitation letters to patients with EHR data showing BP ≥138/88 at their last clinic visit, no hypertension diagnosis, and no antihypertensive medications (Fig. 1). Ineligibility was most commonly because BPs were non elevated at the screening visit. Patient characteristics were like beyond randomization groups, with 48% female, 80% white, mean age 59 years, and mean baseline BP 150/88 mmHg (Table ane). Amidst those randomized to clinic, habitation, and kiosk, 142 (82.6%), 152 (89.4%), and 140 (83.3%) had sufficient BP data for primary analyses (Fig. one , Appendix Tabular array 1). ABPM adherence was like across groups with 91.6% overall completion.

Recruitment, randomization, and follow-up in the BP-CHECK Study. The most common reasons for ineligibility on the follow-upwardly telephone call after invitation messages were sent were going out of boondocks (>2 weeks in the next 2 months), north=509; leaving the health plan, n=174; and unable to converse in English language, northward=174. Abbreviations: BP, claret pressure level; ABPM, 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Compared to mean daytime ABPM, adjusted mean differences in systolic BP were as follows: dispensary (−4.vii mmHg [95% conviction interval −7.3, −2.2]; P<.001); dwelling (−0.one mmHg [−1.vi, 1.five]; P=.92); and kiosk (9.5 mmHg [vii.5, eleven.six]; P<.001) (Table 2). Differences for diastolic BP were as follows: clinic (−7.2 mmHg [−viii.8, −five.5]; P<.001); abode (−0.4 mmHg [−1.4, 0.7]; P=.52); and kiosk (5.0 mmHg [3.viii, half dozen.2]; P<.001). Bland-Altman plots demonstrate the variability of within-person differences (Appendix Figure 1).

Using a diagnostic threshold of daytime mean ABPM ≥135 mmHg systolic or ≥85 mmHg diastolic, 71.7% of participants tested positive for hypertension. Sensitivities for detecting hypertension were 31.1% (95% CI 22.ix, twoscore.6) clinic, 82.2% (73.8, 88.4) home, and 96.0% (ninety.0, 98.v) kiosk. Specificities were 79.5% (64.0, 89.iv) clinic, 53.3% (38.9, 67.2) home, and 28.2% (16.iv, 44.1) kiosk (Tabular array iii). False positive rates were 5.6% dispensary, xiii.viii% home, and 20.0% kiosk.

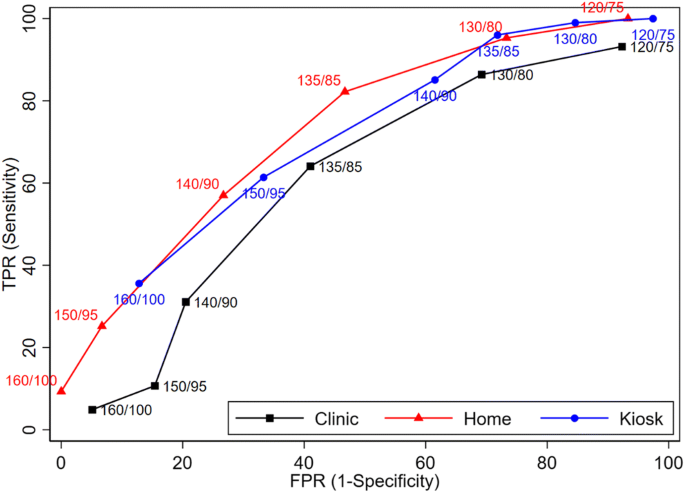

Area under the curve (AUC) analyses for systolic BP (Appendix Figure 2) suggested that HBPM (AUC 0.77, CI 0.69, 0.84) performed meliorate than clinic (AUC 0.64, CI 0.54, 0.71) and similar to kiosk (AUC 0.75, CI 0.70, 0.84) for identifying elevated systolic BP compared to ABPM. For diastolic BP, kiosk (AUC 0.86, CI 0.79, 0.92) performed better than both clinic (AUC 0.75, CI 0.67, 0.83) and HBPM (AUC 0.75, CI 0.67, 0.92). Yet, circumspection should exist used in interpreting these results as hypertension diagnosis is based on either a loftier systolic BP or high diastolic BP and not each value separately. Using a variety of thresholds for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrated that home and kiosk performed better than clinic over a range of BP thresholds (Fig. 2). While diagnostic accuracy was like for home and kiosk, thresholds needed to achieve like sensitivity and specificity were college for dispensary.

Receiver operating feature curves based on paired systolic/diastolic thresholds. TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive charge per unit.

Sensitivity and Exploratory Analyses

Planned sensitivity analyses used changed probability weighting to account for missing outcome information (Appendix Table 2), or were limited to participants adherent to protocol based on a prespecified number of clinic, dwelling, or kiosk BP measurements (Appendix Table 3). Results did not differ from the main analyses. Using ABPM 24-h mean BP with diagnostic threshold ≥130 mmHg systolic or ≥80 mmHg (Appendix Table iv), or ABPM dark BP (Appendix Table v) with diagnostic threshold ≥120 mmHg systolic or ≥seventy mmHg made picayune difference in clinic, home, and kiosk diagnostic operation. Using ACC/AHA thresholds for stage 1 hypertension (systolic BP ≥130 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥80 mmHg) increased hypertension prevalence to 86.ii% and improved the sensitivity of clinic, home, and kiosk, but at the expense of specificity (Appendix Table half-dozen). Very high Clinic BPs (≥160/100 mmHg, specificity 94.9%) provided some assurance that white coat hypertension could exist ruled out (Appendix Table vii).

Subgroup Analyses

Differences between mean daytime ABPM and mean clinic, dwelling house, and kiosk systolic and diastolic BP and diagnostic performance varied little past patient characteristics (Appendix Table A8.a-c).

Intermediate Outcomes

Amid the 71.7% (335/467) of individuals with hypertension based on ABPM testing (reference standard), 40.ix% (137/335) had a hypertension diagnosis recorded in the EHR past their provider betwixt the baseline and 6-month follow-up visit, with no differences by randomization grouping.

Adverse Events

No adverse events related to clinic, dwelling house, or kiosk BP monitoring were reported. ABPM-related adverse events were reported by 36 participants with 39 complaints: arm discomfort (n=20), skin irritation (n=seven), sleep disturbance (n=seven), and feet or restlessness (n=v).

Discussion

In a real-world diagnostic written report conducted in primary care, domicile mean systolic and diastolic BP did not differ significantly from ABPM. In dissimilarity, dispensary BPs were significantly lower and kiosk BPs were significantly college than ABPM.

A systematic review for the USPSTF evaluated the accuracy of role-based BPs compared to ABPM for screening and confirming hypertension.half-dozen, 7 Most merely not all studies plant that office-based BPs were higher than ABPM.six, 7 Virtually studies used automated oscillometric or manual mercury BP monitors with attention to optimal technique and multiple measurements averaged. In our study, BP measurements were mainly past medical assistants every bit part of usual care, typically using aneroid syphyngomanometers. Possible explanations for our finding of clinic BP lower than ABPM include improper measurement technique (due east.g., not inflating gage above true systolic BP, deflating gage too rapidly, difficulties discerning Korotkoff sounds), end-number rounding, and unintentional bias toward lower BP readings.28, 29 Our findings marshal with a cluster randomized trial that found systolic BP 7.five mmHg lower in clinics using manual measurements than clinics with BP measured by validated oscillometric automatic monitors (P<.001), with substantial reductions in finish-number rounding (systolic BP transmission 71%, versus automated 18%; P<.001).30 Routine use of automatic monitors, especially with multiple readings taken over several minutes, could atomic number 82 to average dispensary BPs closer to ABPM;31, 32 yet, this practise is uncommon in the United states of america.33

Another reason that clinic BPs may accept been lower than ABPM in our setting is because BP is rechecked just if the initial BP was >140/90 equally recommended past our healthcare organization and national guidelines.34 This policy, recommended past our healthcare arrangement and national guidelines was informed in role by Handler et al., which analyzed data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys amid 22,641 adults with 3 BP readings.16 Among those with Joint National Commission 7 (JNC7)35 defined stage one hypertension (systolic BP ≥140 to <160 mmHg or diastolic ≥ninety to <100 mmHg) or stage 2 hypertension (systolic ≥160 mmHg or diastolic ≥100 mmHg), 18.2% and 33.five%, respectively, were reclassified to a lower stage using the mean of the 2nd and third BP readings, and less than 0.5% were reclassified to a higher stage. This was interpreted to mean that no additional measures are needed if the first BP is below a threshold, but if the get-go BP is high, information technology should be checked again after 5 min of rest. Criticisms of this newspaper include lack of comparison to ABPM or repeated BPs taken on carve up days. Thus, downward reclassification later on repeated BP measurements may pb to a bias of using the lowest BP instead of the truthful average, which our study suggests.

Lower clinic BPs resulted in lower sensitivity for detecting hypertension than domicile and kiosk. In the USPSTF review,6, 7 initial screening BPs had low sensitivity and moderate specificity for detecting ABPM-confirmed hypertension, with pooled sensitivity and specificity from 15 studies of 54% and 90%, respectively. Nonetheless, confirmatory part-based BPs (i.eastward., after a high screening BP) tended to overdiagnose hypertension with pooled sensitivity and specificity from 8 studies of 80% and 55%.6, 7 These results are in sharp dissimilarity to our study, with clinic sensitivity 31.1% and specificity 79.v%. The negative likelihood ratio (calculated from both sensitivity and specificity) was close to 1.0, indicating that a clinic BP less than 140 mmHg systolic and 90 mmHg diastolic (negative examination) had little impact on the likelihood that the ABPM would be negative. Our written report suggests that confirmatory BPs in clinic, equally practiced in routine care, may exist more than likely to underdiagnose than overdiagnose hypertension.

Home BP was similar to ABPM. BP is highly variable, particularly amidst individuals with untreated hypertension, with systolic oftentimes varying by thirty–40 mmHg or more during daytime hours.36 Home provided many more BPs, with boilerplate standard departure smaller than single or duplicate clinic measurements. Home had higher sensitivity than clinic for detecting hypertension, only at the expense of specificity. Withal, as most participants had hypertension, false positive rates were relatively low. Our Home BP results are like to those reported by the USPSTF review,6, 7 which had HBPM pooled sensitivity and specificity 84.0% and lx.0%, respectively. While ABPM is considered the "gilt standard," controversy remains.27 Both ABPM and HBPM are more predictive of cardiovascular events than dispensary BPs. Three studies demonstrated that ABPM more closely correlates with left ventricular hypertrophy/mass than HBPM.37,38,39 However, no trials accept compared the effectiveness of ABPM and HBPM in preventing CVD events.

Mean systolic and diastolic BPs were significantly higher for kiosk than ABPM. Kiosk diagnostic accuracy was nonetheless improve than clinic across a range of BP thresholds. The BP kiosk we used was validated against mercury manometers.19 Another report compared it to ABPM,20 with 100 individuals without treated hypertension taking triplicate kiosk BP measurements at local pharmacies on 4 separate days. Kiosk BP was only slightly higher than ABPM (by 2.three±9.v mmHg systolic, 2.2±6.9 mmHg diastolic). Kiosks in our written report were often in decorated waiting rooms, possibly leading to higher BPs. While participants were instructed to residue 5 min before measurements, nosotros are non certain they did. Boosted written report could determine if protocol or equipment adjustments (e.g., rest period, tranquility location) improve BP kiosk performance.

Our study used ACC/AHA stage 2 recommendations for making a new diagnosis of hypertensionv. Using ACC/AHA phase ane BP thresholds, 86% of our population tested positive for hypertension. The ACC/AHA guidelines recommend lifestyle behavior modify to lower BP for individuals with stage one hypertension at low take a chance for CVD and antihypertensive medications for those at moderate-to-high CVD risk. Almost of our population was at moderate-to-high CVD take chances and would qualify for antihypertensive medications at the lower stage ane threshold.5, 40

Even though home BP monitoring performed improve than clinic and kiosk, many implementation challenges remain. The tools we used to systematically collect and average home BPs (Bluetooth connectivity and a database for averaging BPs) are not typically available in chief care. Furthermore, although participants and their physicians received ABPM results and the diagnostic interpretation of the test, simply 41% of those with a positive test had a hypertension diagnosis recorded in the EHR by 6 months. Nosotros know of just one implementation study that is testing unlike strategies for improving hypertension diagnosis, with results not yet published.41 This US report is testing a multilevel strategy that includes provider presentations, patient information, nurse training for pedagogy patients to conduct HBPM, EHR-embedded clinical decision support, and increased access to a culturally adapted ABPM service. Results of this study might inform next steps for improving hypertension diagnosis.

Limitations

Study limitations were showtime, since the study was conducted at a single healthcare organization, results might differ at other settings with different standards for measuring BP, such as use of automated BP. 2nd, African American and other racial/ethnicity groups were underrepresented. Tertiary, although the accurateness of all BP monitors used was validated past established protocols, results might differ with other monitors.42 Fourth, participants were aware of their diagnostic group consignment and that they had loftier BP. Contextual and behavioral factors might have influenced BP diagnostic results. Fifth, diagnostic functioning may accept differed if we included individuals with lower BPs. Sixth, statistical comparisons of AUCs for ROCs of systolic or diastolic BP between diagnostic methods and the reference standard should be interpreted charily because the diagnosis of hypertension is based on both systolic or diastolic BP, rather than considering each measure out separately, and thresholds for diagnosing hypertension differ across guidelines and subgroups. Last, assessment of comparative performance beyond measurement methods might have been more than robust if participants had completed all three diagnostic regimens. However, our study compared hypertension diagnosis methods as used in real-world settings, which would not exist possible with that study design.

CONCLUSIONS

In this diagnostic report, compared to ABPM, dispensary had significantly lower and kiosk significantly college mean BP measures. HBPM was not significantly unlike, lending further credibility to the utility of home measurements. About participants with loftier BP on screening and ABPM diagnostic testing did not receive a hypertension diagnosis. New strategies are needed to better hypertension diagnosis.

References

-

Han L, You D, Ma W, et al. National trends in American Heart Association revised Life's Simple 7 metrics associated with hazard of mortality amongst US adults. JAMA network open. 2019;2(10):e1913131.

-

M. B. D. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative take chances assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Affliction Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659-1724.

-

Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, et al. Trends in blood force per unit area control among The states adults with hypertension, 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1190-1200.

-

U. S. Preventive Services Chore Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for hypertension in adults: U.s. Preventive Services Task Forcefulness reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(sixteen):1650-1656.

-

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: a Study of the American Higher of Cardiology/American Eye Clan Task Force on Clinical Practise Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138(17):e484-e594.

-

Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Webber EM, Coppola EL, Perdue LA, Weyrich MS. Screening for hypertension in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the United states Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;325(16):1657-1669.

-

Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Webber EM, Coppola EL, Perdue LA, Weyrich MS. Screening for hypertension in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Job Force. AHRQ Publication No. xx-05265-EF-1: Prepared for the Bureau of Healthcare Enquiry and Quality and the U.Southward. Department of Homo and Wellness Services; 2020:Evidence Synthesis 197.

-

Kronish IM, Kent S, Moise N, et al. Barriers to conducting ambulatory and home blood force per unit area monitoring during hypertension screening in the Usa. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;xi(9):573-580.

-

Cohen JB, Padwal RS, Gutkin G, et al. History and justification of a national claret pressure measurement validated device listing. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):258-264.

-

Muntner P, Einhorn PT, Cushman WC, et al. Blood pressure cess in adults in clinical practise and clinic-based research: JACC Scientific Expert Console. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(3):317-335.

-

Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Centre Association. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):e35-e66.

-

Green BB, Anderson ML, Campbell J, et al. Blood pressure checks and diagnosing hypertension (BP-CHECK): design and methods of a randomized controlled diagnostic study comparing clinic, home, kiosk, and 24-hour convalescent BP monitoring. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;79:1-13.

-

El Assaad MA, Topouchian JA, Darne BM, Asmar RG. Validation of the Omron HEM-907 device for blood pressure level measurement. Blood Printing Monit. 2002;7(4):237-241.

-

Ma Y, Temprosa Chiliad, Fowler Due south, et al. Evaluating the accurateness of an aneroid sphygmomanometer in a clinical trial setting. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(3):263-266.

-

de Greeff A, Reggiori F, Shennan AH. Clinical cess of the DINAMAP ProCare monitor in an developed population co-ordinate to the British Hypertension Guild Protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12(i):51-55.

-

Handler J, Zhao Y, Egan BM. Touch of the number of blood pressure measurements on blood pressure level classification in Us adults: NHANES 1999-2008. J Clin Hypertens. 2012;14(11):751-759.

-

Altunkan S, Ilman North, Kayaturk N, Altunkan Due east. Validation of the Omron M6 (HEM-7001-E) upper-arm blood pressure level measuring device according to the International Protocol in adults and obese adults. Claret Press Monit. 2007;12(4):219-225.

-

Nunan D, Thompson 1000, Heneghan CJ, Perera R, McManus RJ, Ward A. Accuracy of self-monitored claret pressure for diagnosing hypertension in primary care. J Hypertens. 2015;33(4):755-762.

-

Alpert BS. Validation of the Pharma-Smart PS-2000 public utilize claret pressure monitor. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9(1):nineteen-23.

-

Padwal RS, Townsend RR, Trudeau L, Hamilton PG, Gelfer M. Comparison of in-chemist's shop automatic blood pressure kiosk to daytime convalescent claret pressurein hypertensive subjects. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;nine(2):123-129.

-

Westhoff Th, Schmidt Southward, Zidek W, van der Giet M. Validation of the Stabil-O-Graph claret pressure level self-measurement device. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22(three):233-235.

-

Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3621.

-

Bromfield SG, Booth JN, 3rd, Loop MS, et al. Evaluating dissimilar criteria for defining a complete ambulatory blood pressure monitoring recording: data from the Jackson Heart Written report. Blood Printing Monit. 2018;23(2):103-111.

-

Liang K, Zeger S. Longitudinal information analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:xiii-22.

-

Levin J, Serlin R, Seaman MA. A controlled, powerful multiple-comparing strategy for several situations. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:153-159.

-

Muntner P, Carey RM, Jamerson K, Wright JT, Jr., Whelton PK. Rationale for ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring thresholds in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Clan guideline. Hypertension. 2019;73(1):33-38.

-

Shimbo D, Abdalla Thou, Falzon L, Townsend RR, Muntner P. Role of ambulatory and home BP monitoring in clinical practice. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):691-700.

-

Kallioinen N, Hill A, Horswill MS, Ward HE, Watson MO. Sources of inaccuracy in the measurement of developed patients' resting blood pressure in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2017;35(3):421-441.

-

World Wellness System. WHO technical specifications for automated non-invasive blood pressure measuring devices with gage. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2020: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331749/9789240002654-eng.pdf.

-

Nelson MR, Quinn S, Bowers-Ingram L, Nelson JM, Winzenberg TM. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of oscillometric vs. manual sphygmomanometer for claret pressure level direction in chief care (CRAB). Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(6):598-603.

-

Myers MG, Matangi Chiliad, Kaczorowski J. Comparison of awake convalescent blood pressure and automatic office blood pressure using linear regression analysis in untreated patients in routine clinical exercise. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2018;20(12):1696-1702.

-

Roerecke Chiliad, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-assay. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):351-362.

-

Todkar S, Padwal R, Michaud A, Cloutier L. Noesis, perception and practice of health professionals regarding claret pressure measurement methods: a scoping review. J Hypertens. 2021;39(iii):391-399.

-

American Middle Association, American Medical Clan. Mensurate Accurately. https://targetbp.org/blood-pressure-improvement-program/control-bp/measure out-accurately/.

-

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black Hour, et al. The seventh study of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Claret Pressure: the JNC vii report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560-2572.

-

Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi C, Salvi P, Bilo G. Cess and interpretation of blood pressure variability in a clinical setting. Blood Press. 2013;22(6):345-354.

-

Zhang Fifty, Li Y, Wei FF, et al. Strategies for classifying patients based on office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure measurement. Hypertension. 2015;65(half dozen):1258-1265.

-

Anstey DE, Muntner P, Bello NA, et al. Diagnosing masked hypertension using ambulatory claret force per unit area monitoring, habitation blood pressure monitoring, or both? Hypertension. 2018;72(5):1200-1207.

-

Schwartz JE, Muntner P, Kronish IM, et al. Reliability of office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure measurements and correlation with left ventricular mass. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2911-2922.

-

Dart Research Group, Wright Jr JT, Williamson JD, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116.

-

Kronish IM. Implementing hypertension screening guidelines in principal care. 2018; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03480217.

-

Stergiou GS, Palatini P, Asmar R, et al. Recommendations and practical guidance for performing and reporting validation studies co-ordinate to the Universal Standard for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices past the Association for the Advocacy of Medical Instrumentation/European Order of Hypertension/International Organization for Standardization (AAMI/ESH/ISO). J Hypertens. 2019;37(3):459-466.

-

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Boston University. Framingham Center Study risk functions: cardiovascular illness (10-year adventure). 2020; https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-take chances-functions/cardiovascular-disease-10-twelvemonth-adventure/.

-

D'Agostino RB, Sr., Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular gamble contour for use in primary care: the Framingham Middle Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753.

-

Gaziano TA, Young CR, Fitzmaurice G, Atwood S, Gaziano JM. Laboratory-based versus non-laboratory-based method for cess of cardiovascular illness run a risk: the NHANES I Follow-upwardly Report cohort. Lancet. 2008;371(9616):923-931.

-

Green BB, Anderson ML, Cook AJ, McClure JB, Reid R. Using body mass index data in the electronic health tape to calculate cardiovascular risk. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(4):342-347.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of Chris Tachibana, PhD, for scientific editing. We acknowledge the research study team: Camilo Estrada, AA; Ron Johnson, MA; Ann Kelley, MHA; Miriam Marcus-Smith, RN, MHA; Stephen Perry, BS, Stacie Wellwood, LPN, AS; and Margie Wilcox, for their work on recruiting and conducting inquiry visits, and project manager Christine Mahoney, MA, for her contributions in developing and launching information collection. We thank the Kaiser Permanente Washington primary care medical centers that immune us to enroll their patients and provided space for research visits. We also acknowledge our patient and stakeholder advisory commission for their help in planning the written report and interpreting the study results. Nosotros recognize Jerry Campbell, BS, who contributed to the concept, design, and inquiry processes as a patient co-investigator prior to his expiry in 2019.

Funding

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Plan Award (CER-1511-32979). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and practise not necessarily represent the views of PCORI.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations one. The North American Main Intendance Research Group Annual Coming together, November 24, 2020, webinar, oral presentation selected equally one of the top 3 abstracts of the meeting. two. The Healthcare Systems Inquiry Network Annual Meeting, May xi, 2021, webinar, oral presentation.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution four.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long equally you give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and point if changes were made. The images or other tertiary party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If textile is not included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended utilize is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, y'all will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Green, B.B., Anderson, One thousand.L., Cook, A.J. et al. Dispensary, Domicile, and Kiosk Blood Pressure Measurements for Diagnosing Hypertension: a Randomized Diagnostic Study. J GEN INTERN MED (2022). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11606-022-07400-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07400-z

KEY WORDS

- hypertension

- diagnosis

- blood pressure level determination, blood force per unit area monitoring, ambulatory

- claret force per unit area monitoring, abode

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-022-07400-z

0 Response to "what measurement is used to study blood pressure"

Post a Comment